It was my classes’ last seminar in our unit on The Watsons Go To Birmingham – 1963, a wonderful novel about a family from Michigan — in particular, two quarrelsome brothers, Kenny and Byron — and what happens to them when a visit to their grandmother in Birmingham, Alabama, coincides with an epoch-defining act of racial terrorism.

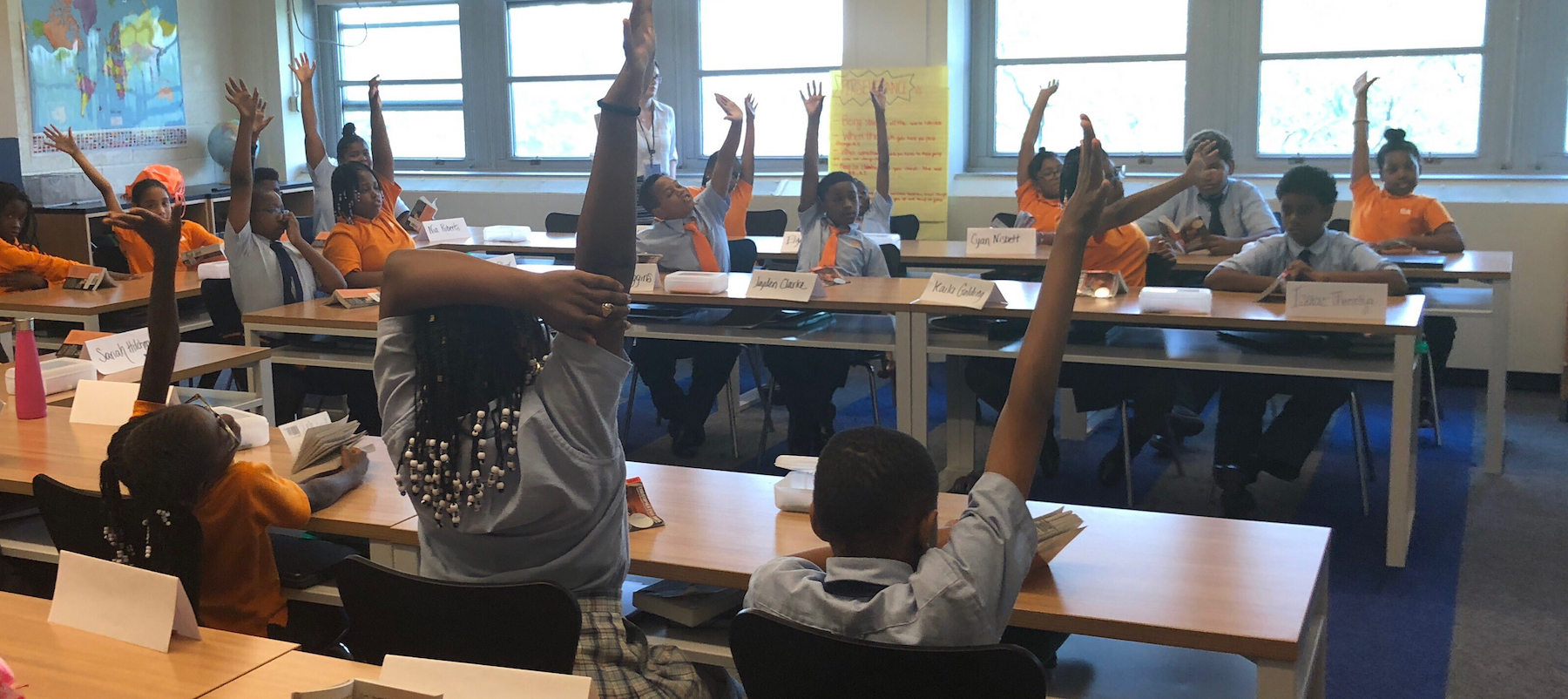

My fifth graders at SA Queens Middle School were divided into small groups, each responsible for finding evidence to support one of the novel’s big themes which we had been discussing over the past three weeks, and which they would present to the class. I approached one group of scholars, who were discussing the theme of growing up, and how it presents opportunities to become a better person.

“One piece of evidence is how Kenny and Byron’s relationship changes from the beginning to the end,” said one scholar. “After Byron goes to his Grandma’s and gets disciplined, he starts to be more open and polite.”

“Oh, yes!” jumped in another. “It’s like he’s trying to be more caring. Since he turned 13, Byron had been so rude and acting like he’s so cool. But after Birmingham he’s more polite…more caring…more open…”

“It’s like he becomes less selfish!” offered a third. “Byron matures and becomes less selfish. And that changes his relationship with Kenny.”

“Great insights scholars!” I smiled at them. “Can you find evidence in the text that supports those ideas?” As the group dove into the book searching for quotes, I moved away.

This is my second year teaching fifth grade, and once again, teaching The Watsons Go to Birmingham is a highlight. This is the first novel scholars read and study together as middle schoolers, and it is an introduction to the kind of literary discussion and analysis they will do throughout middle and high school. The book is dramatic — the narrator Kenny, an 11-year old African-American boy, comes face to face with the Birmingham church bombing that left four African-American girls dead — but it is also deeply relatable. The climactic event is set against the intimate backdrop of his loving family and standard coming-of-age tribulations — challenges at school, ups and downs with friends, and fights with siblings. Kenny’s everyday struggles are similar to those our fifth graders are beginning to encounter, and as they become invested in the story of Kenny and his family, a chapter in civil rights history comes to life for them.

Before we began reading the novel, we read contemporary commentary and poetry about the Birmingham bombing, to fill in essential background knowledge. While most scholars were familiar with civil rights heroes like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, few knew the details of this event. Even as we discussed the bombing and the historical context, it remained largely abstract.

But as scholars listened to a recording of the novel in class, there were audible gasps when the bombing occurs. Scholars experienced the shock of the event as Kenny does: his confusion as he runs to the church to discover what has happened, his benumbed efforts to find his sister Joetta among the rubble, and his slow awakening to the fact of her survival — thanks to his own semi-mystical, semi-heroic actions.

The book is filled with layers of meaning: there are symbolic elements that the scholars must unpack in order to understand. It’s like solving a mystery, and ferreting out the clues of meaning makes them all the more passionate about the book.

Ultimately, The Watsons Go to Birmingham is about overcoming adversity. All people face hardships — the question is how do we respond? Scholars learn the answer to this question along with Kenny. They feel his fear, his courage, and his trauma, and they take part in his healing in the bosom of his family’s love. As they do, they experience what is best about reading: an expansion of our capacity for empathy and compassion as we live — if only in our imaginations — another person’s experience.

All people face hardships — the question is how do we respond?

Literary experiences like these are what make us fall in love with reading, and watching my scholars’ blossoming passion is why I love teaching this unit. Recently, one of my students approached me and said, “Before this year I did not like ELA and I did not like reading. But now that I’m taking this class, I love reading.”

A teacher couldn’t ask for anything more.