It’s the first day of Jess Johnson’s U.S. History class. Her sixth graders are looking at her expectantly, waiting to start learning about King George III or the lost colony of Roanoke.

Instead, class starts with much more recent history — an assignment for scholars to tell the story of their birth.

Eagerly, they write down the details of everything they know, from the date and time they came into the world to what the weather was like, who was in the room, how long the labor lasted, how their parents decided on a name.

As the students are writing, Ms. Johnson starts asking questions. “How do you know all this?” she asks. “Do you remember it all? Who took the photos that day? Was there anyone else in the room who might remember it differently?”

“This is how I want students to approach the study of history,” said Ms. Johnson. “Even if you witness an event, you don’t have the full story — just one perspective. Right away, I want kids thinking about the construction of truth, and how history looks different when you change the lens.”

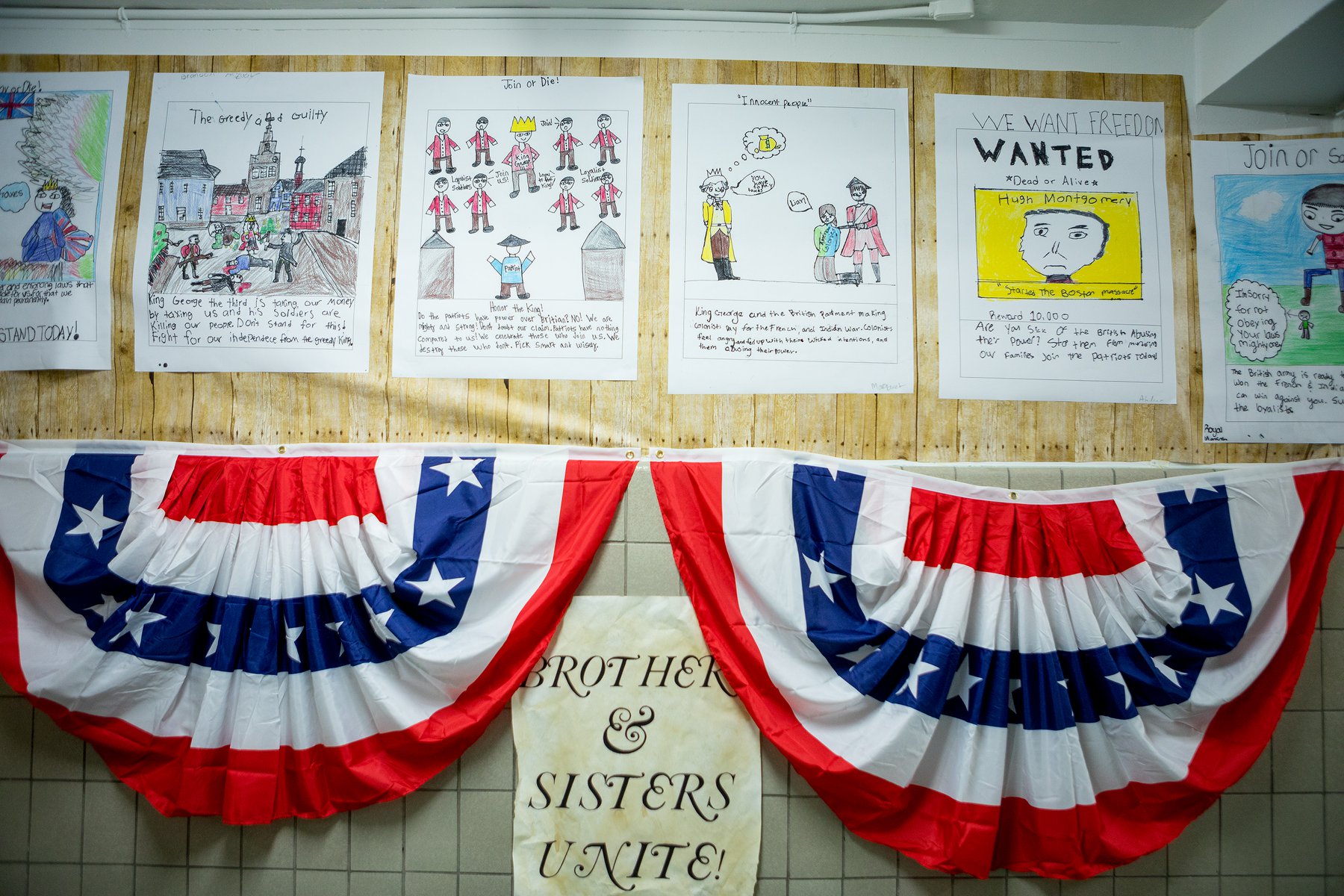

That mindset is the foundation of Success Academy’s middle school U.S. History curriculum. The curriculum, which has no textbook and uses only primary and secondary sources and analyses, pushes students to think critically about history, actively interrogating and inquiring the accounts put before them.

“This way of teaching history helps kids make connections to historical events throughout time, rather than seeing history as a disjointed series of events,” Ms. Johnson said. “We were recently talking about Andrew Jackson, and one of my scholars compared him to Alexander the Great, who they haven’t heard or talked about in over a year. The same ideas and themes are repeated over and over again in different societies across history, and this curriculum really allows scholars to recognize that and think about what that means for their own lives today.”

Each day, the lesson is grounded in a central question or theme that scholars explore throughout the unit. On a recent morning, that question was: “To what extent did President Andrew Jackson promote democratic values?”

Kids’ hands shot up.

“Who are we talking about?” one sixth grader asked. “If we’re talking about democracy for white men, President Jackson definitely promoted democratic values for them, because he gave more of them the right to vote. But if we’re talking about African-Americans, or women, or Native Americans, he really did nothing to expand their rights.”

His peers nodded in agreement. “What about the Indian Removal Act?” one student added. “He forced Native Americans to move after the Supreme Court said they had a right to stay in Georgia. Based on everything we’ve learned about the Constitution and the equal branches of government, isn’t that super undemocratic?”

Reflecting on the exchange, Ms. Johnson sees students adopting the habits of great historians.

“We’re not teaching them what to think. We’re teaching them how to think,” she said. “Pre-teens are good at questioning authority and push against the system. Our model lets them flex that muscle in history class. We’re mirroring their adolescent development and teaching them how to grow up. If you want something, you need to construct a valid argument for it, cite evidence and consider multiple perspectives.”

“If you want something, you need to construct a valid argument for it, cite evidence and consider multiple perspectives.”

It’s working. Ms. Johnson’s students are able to not only think critically about the past, but also connect the stories of the past they’re learning about to their current realities. They recognize the ways that slavery continues to impact African-American families, through mechanisms like intergenerational wealth inequality and lack of access to affordable housing. They trace the roots of gender inequity from the colonies to today. They study the geopolitical rifts between the north and the south and the impact those differences from centuries ago continue to have.

As they do, they begin to hone their opinions and worldviews. “We did a project on lesser-known historical figures, people other than Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, the ones we always hear about,” Ms. Johnson said. “And the kids really understood, and were angered by, the fact that the people we did our projects on did amazing things but aren’t as prominent because they’re not the ones who had the power to ensure their stories were told. They’re not the ones whose stories were recorded.”

As they’re learning, Ms. Johnson is careful to remind her scholars to put themselves in the shoes of people with different views, and to be critical of their own perspectives when necessary. “It’s crucial that they understand why some people might feel differently than they do and be able to sit at the table together and have that discussion,” she said. “It can be a really challenging thing to look at someone you disagree with and say, ‘I understand where you’re coming from,’” she said.

“But they do it every day, better, I think, than most adults can. To see 10- and 11-year-olds develop those skills is one of the most powerful things I’ve ever witnessed.”

Pictured: Jess Johnson (pink cap) with scholars from her class.

To explore Success Academy’s full middle school U.S. History curriculum and e-courses for free, visit the Ed Institute website.

This post was originally published online at the Robertson Center.